Nuneaton-based photographer Connor Richardson talks about art, decay, and the role of graffiti as a creative outlet.

From the window, you can see the mouth of an industrial estate backing onto the estate. The houses directly outside are flat terraces with flaking walls. This is Nuneaton, a working-class town in Warwickshire that has fallen on hard times.

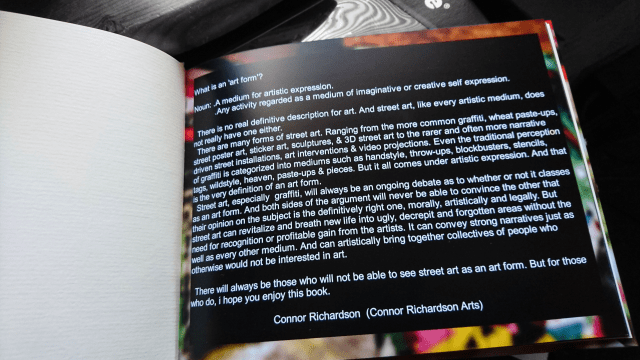

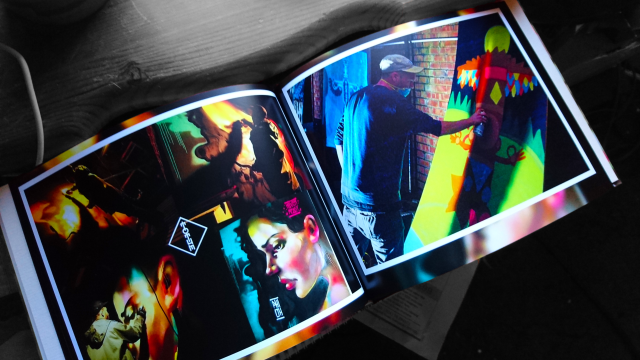

Connor has focussed his energies for his new photobook, The Criminalization of Art, on street art and graffiti in and around Nuneaton. From cover to cover, the book is filled with photos of crumbling walls made brighter with huge, garish designs.

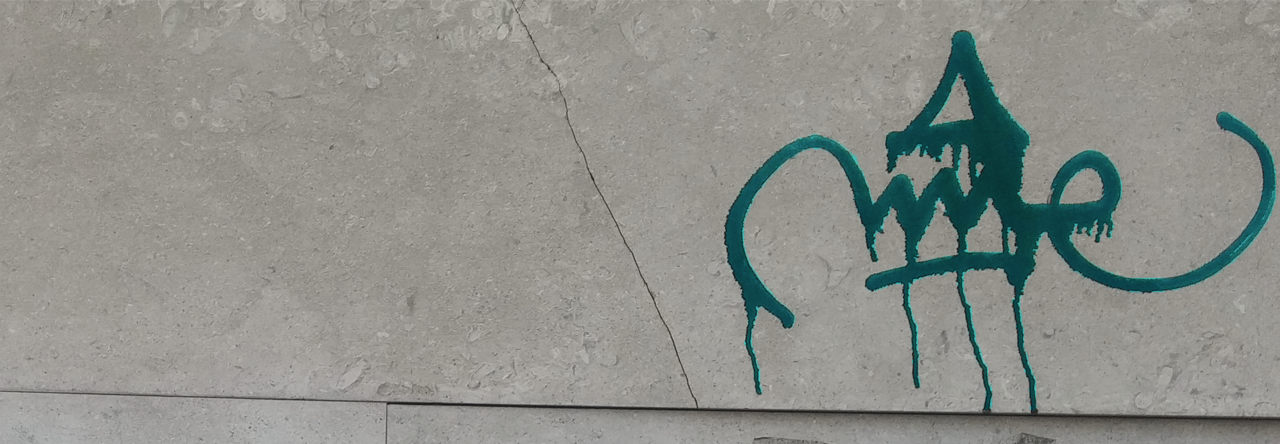

Some of them are highly political- a swallow with a bomb for a head dives towards the ground in one – and others are more traditional ‘tags’, highly stylised personal brands and names in enormous colourful fonts.

Nuneaton is the barely-beating heart of austerity Britain.

I asked Connor how much being brought up in Nuneaton had influenced his decision to capture street art.

“A good quote that has always stuck with me,” he said, “which I find relevant to street art in this town, is Ernst Fischer: ‘In a decaying society, art, if it is truthful, must also reflect decay’

“Having come from this kind of town, [and recognised that] there is a lot of decay here… that has helped me realise the potential in terms of beauty behind such run-down kinds of scenes.”

Connor hasn’t always been a photographer- he started out drawing and painting, but segued into photography when he got bored of other mediums:

“I had been drawing for so long, I just needed another outlet, another way of expressing myself… with photography being completely different to traditional forms of art just… I took to it, really.”

The inspiration for his style is diverse. Connor cites both the gritty, documentary styles of Sally Mann and the surrealist and painting-like works of Ellen Rogers as influences

“[Ellen Rogers] uses a very interesting colour palette… she uses very old format cameras, which bring a very vintage feel to it. I’ve tried achieve this in some of them photos, by using some very lo-fi cameras, low end toy cameras, stuff like that.”

His work is in some ways a critical response to the teaching he received in photography from his days at Coventry University:

“Having gone college and university, you’re only ever really exposed to the more traditional forms of art: pretty paintings, pretty photos with pretty people in, and pretty landscapes.

“I’ve always had a disconnect from that. There was nothing I could really relate to. Having come from a town like this… I kind of found the beauty in the decay of it all.”

For Connor, it is important that art is truthful; especially concerning his photography. I asked him if he had done any of the street art featured in his photos himself:

“None of them- I wanted to portray other people’s work. I thought it would be a bit more truthful.

“One of the points I make in the book – and one of the main reasons I like street art – is that it’s done without any recognition, or any forms of profitable gains for the artist.

“It is an expression of their work that they are willing to put up for free, for anybody to view. It’s not like you’re putting out work for the sake of recognition.”

The truth in this is undeniable- if street artists owned up to their work, the police would have a field day. It’s easy to forget that the law considers all forms of graffiti and street art as vandalism, and that there are huge costs incurred to local councils in cleaning it up.

In 2007 The Chronicle, a daily newspaper from the North East, reported a £1.3m spend over the course of one year of trying to remove graffiti. In Newcastle, anti-graffiti squads were called up to 15 times a day.

“There are some buildings and some locations which I don’t believe should be used as a medium for street art,” Connor said.

“I understand the moral issues around it, but it is going to exist either way… I do think it is important to document them while they last.

“It’s a matter of enjoying it. That’s all street art is. A lot of people will walk past, see a mural, see a piece… and they’re just happy looking at it, walking past it.

“That’s what you need to do with the book as well. Enjoy it.”

You can purchase The Criminalization of Art by contacting Connor through his Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/connorrichardsonarts/